The developed economies of the world fell hand in hand into the harsh inflation cycle which peaked in 2022. This was primarily due to supply chain constraints driven by the COVID pandemic.

Some were more wounded than others by the fierce rates hikes brought on by central banks.

It is consensus now that the peak of higher borrowing costs is behind us.

Through the rate-hike maze, the developed economies lost touch with each other, with some more economically discombobulated than others.

We now see the unwinding of the tightening likely to happen – with a lot less synchronization than on the way up (Swiss National Bank having already cut!).

The effects of higher interest rates were drastically different for these economies, hence the ability for their respective central banks to cut interest rates widely vary in magnitude and speed across the economies.

Whilst the Fed leads the pack on the way up, we don’t think this will be the case on the way down.

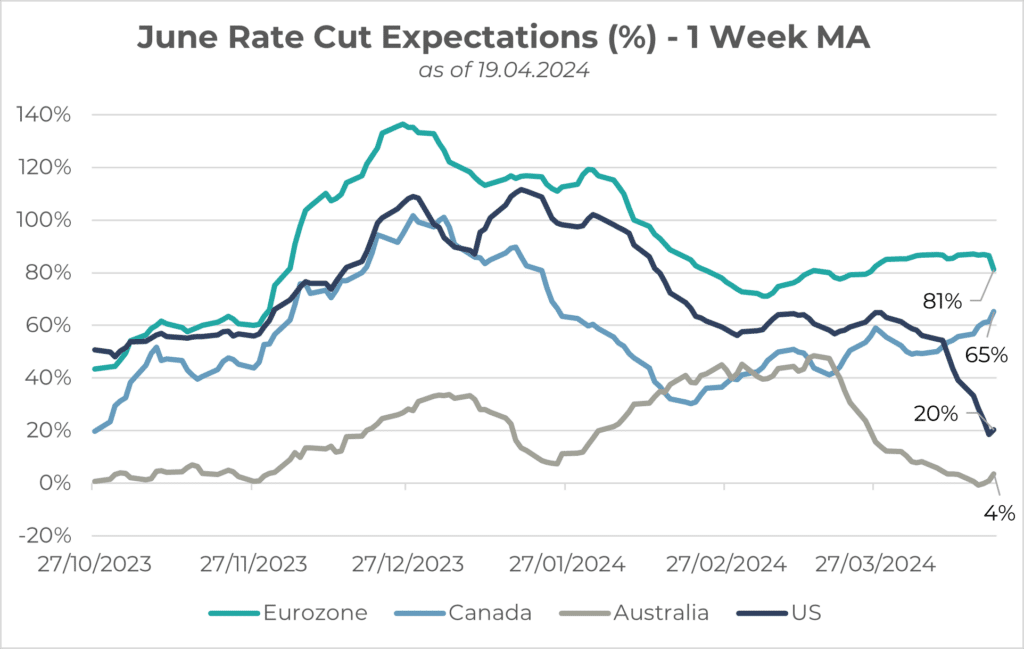

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

In very late 2023, the US, Eurozone and Canada were all sitting at or above 100% chance of a rate cut. This has dramatically changed since, with positive economic surprises for the US dropping that probability to 20% as of the 19th of April. Europe is further along in its cycle, with its largest constituent Germany having dropped into a heavy manufacturing recession in 2023 following more specific energy impacts from the Russia-Ukraine war.

A Snapshot of Developed Economies State

There are major differences in the composition of economic growth across these countries, with Europe relying more heavily on manufacturing, US a more consumer-lead, services economy and Canada/Australia still having a heavy services component – though being very influenced by commodity cycles. This makeup, alongside other factors such as number of floating rate mortgages for households, demographics, productivity, fiscal support, and leverage, makes these economies react very differently to increased borrowing costs – both on the household and corporate side.

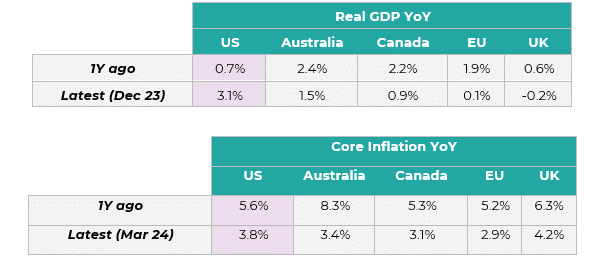

The current state compared to 1Y ago:

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

US Brilliance

Before we understand why the US has been so resilient, it is important to note that in general, due to the huge deleveraging of global economies following the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, the overall fragility of these systems have decreased – hence being less prone to growth shocks following rate hikes.

The US is a clear standout, with the latest real GDP print at 3.1%. Disinflation has clearly been trending downwards for most economies quite well except for the UK who have taken on troublesome wage growth issues. Whilst the core inflation in the US is at 3.8%, 33% of this is shelter whilst in Australia for example, it only accounts for ~6%. This shelter component is quite lagging, and we have clear evidence of “real-time” indicators of shelter inflation coming down, bringing a more realistic core inflation measure to below 3%.

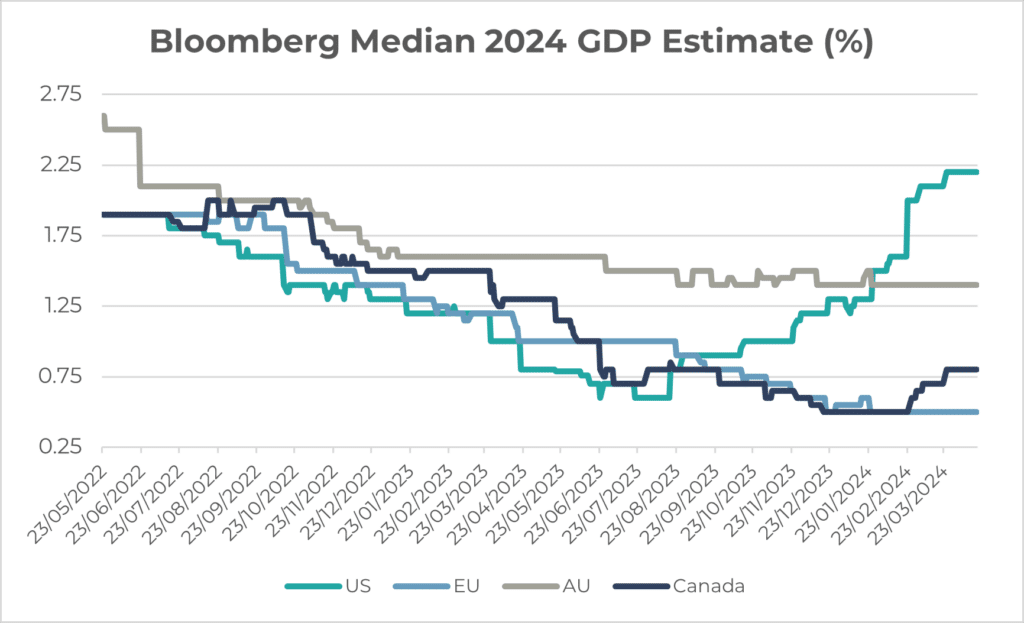

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

Above shows the revisions to the estimates for real GDP in 2024 for these economies, illustrating the upside surprises to the US economy from a growth perspective. We believe the primary reasons for this are due to 3 main themes:

- Stimulus remains from the previous years (Consumer Excess savings): Enormous pandemic fiscal support still existed in the system, filling consumer pockets with cash aid.

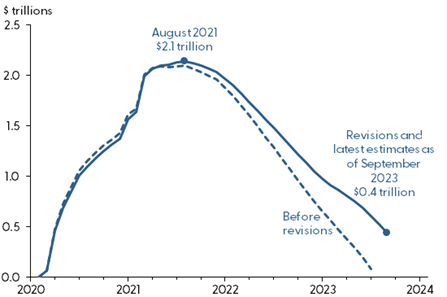

Excess savings

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

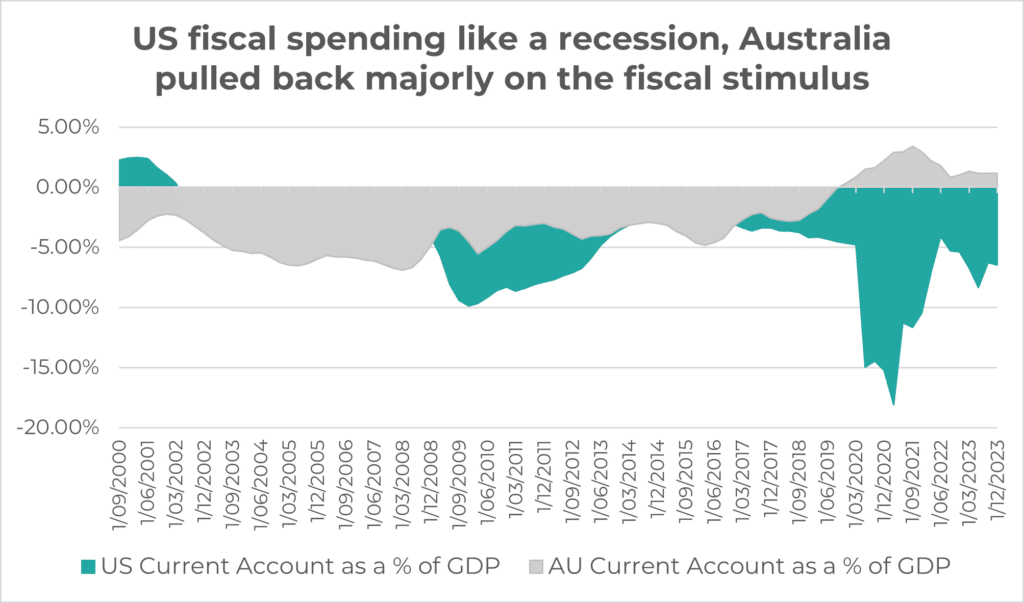

2. Large Fiscal Spending (Labour Support): Similar to A, the US ran a 6-7% GDP fiscal deficit (government spending), which supports job growth, consumer relief, government social benefits (support for student loans, the Biden inflation reduction act) and core services (transport, education, and healthcare).

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

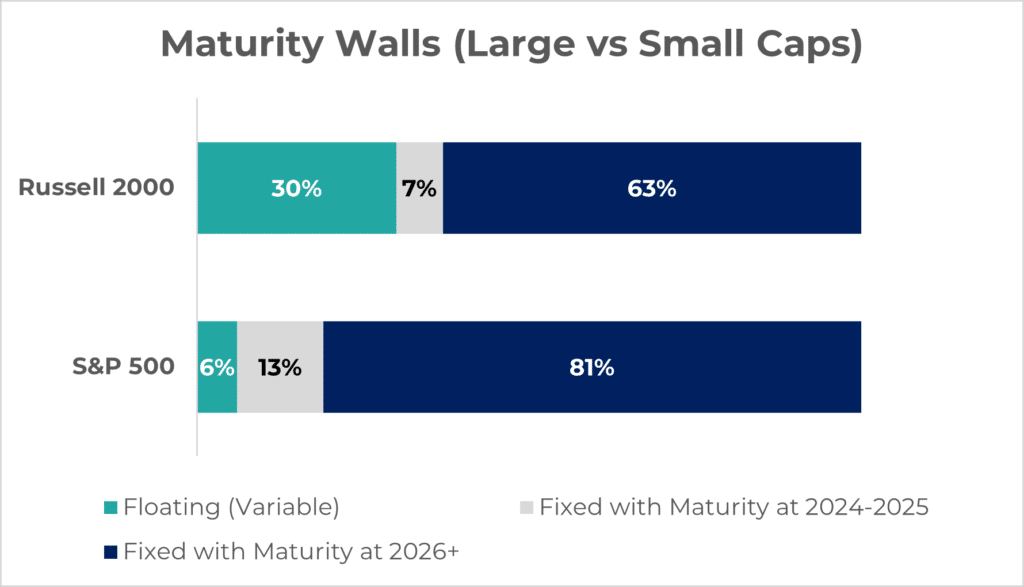

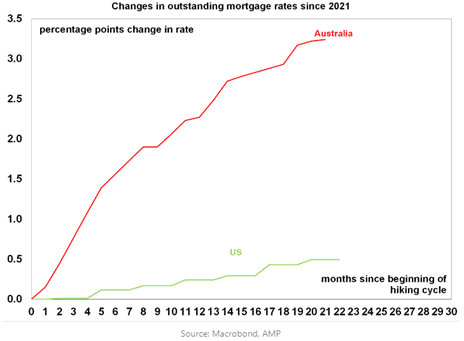

3. Long Debt Maturity Profiles: Both households and corporates spent many years with 0-2% Interest rates, where they locked in long term (5-10Y for corporates, and 30Y for households’ mortgages) at very low rates. This naturally makes their interest-rate sensitivity low and disposable income high.

- Seen below, 81% of the S&P 500 have 2026+ maturities on their debt fixed, showing how economic sensitivity in the large cap sector is low.

- Mortgage servicing has also been shown to not have been fully impacted, as 90% of US are on fixed-rate (75% on 30Y) mortgages. 30% of the population rent as well.

Source: Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

Why aren’t cracks fully in place for other economies then?

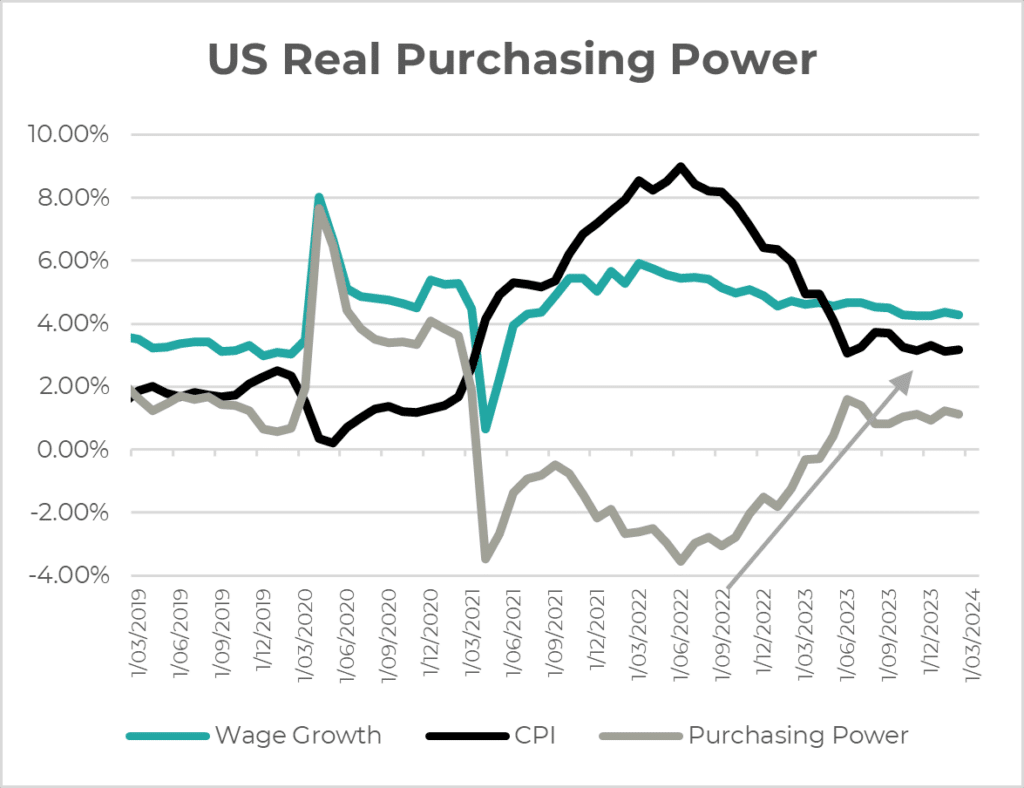

A positive factor for all economies has been the increase in Real Purchasing Power during the disinflation trend (we’ll paint an example of the US below). Many of these economies have enjoyed rising wages against falling inflation YoY, which has supported disposable income for consumers till now.

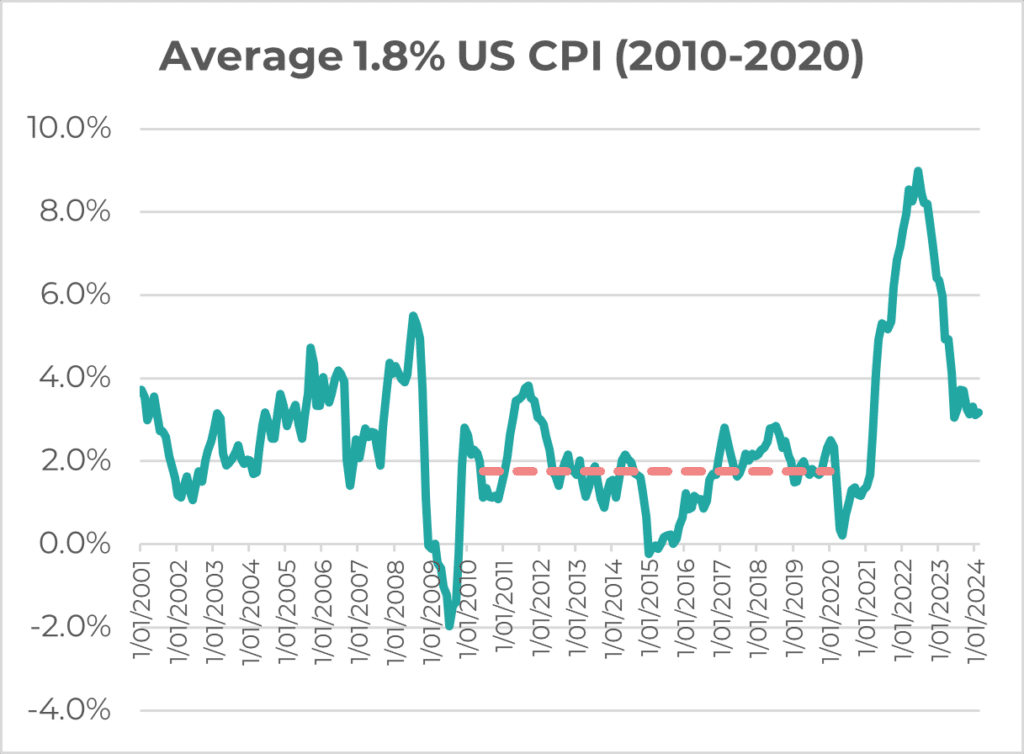

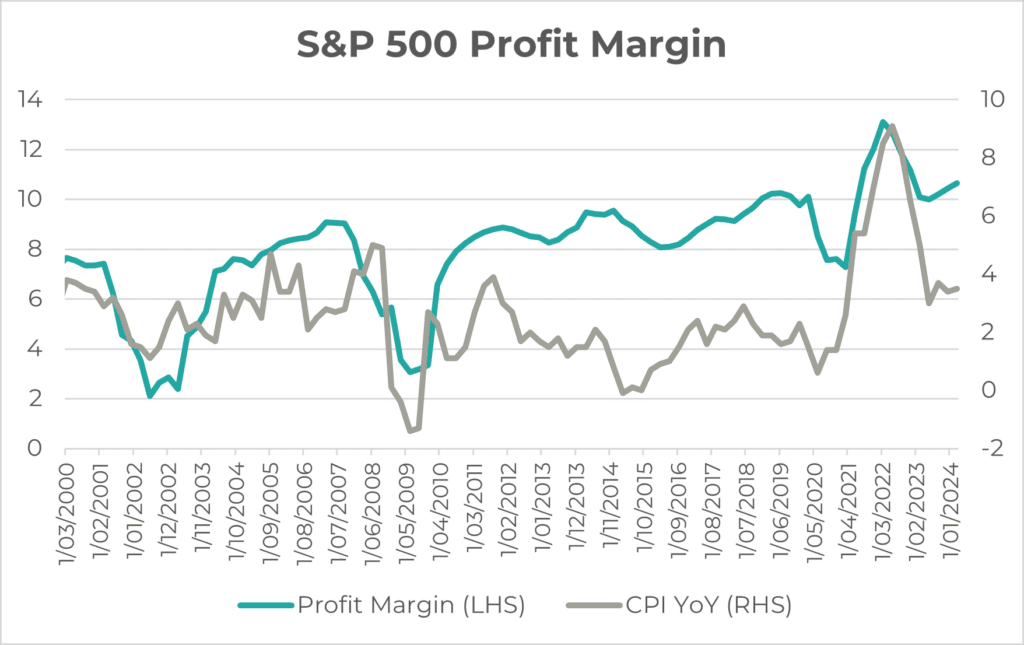

The narrative around inflation was constantly painted as a negative picture during the 2022 wave, though one must understand that inflation before 2020 was extremely low and difficult to get rising following the GFC where there was a massive deleveraging of the system. When inflation rises, prices of goods and services increase, but this actually means companies’ top-line growth increases (revenue). Whilst it may also mean that their costs are higher (PPI), margins of companies got to very high levels during the 2021 period, and hence the starting point was extremely elevated. The surprise was that consumers were able to bear the price rises and continued to spend in ways that economists and investors did not expect, and since 70% of US GDP is consumption, growth kept up.

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

No wonder the ex-US nations are expected to cut earlier.

Clearly it makes sense for the European Central Bank and the Bank of Canada to consider cutting rates much earlier than the Fed. The debt in these countries is starting to mature for households, interest rates are still high, and households are feeling more pressure.

Above is an example of Australia’s outstanding mortgage rates. This gap against the US who lock in 30Y fixed-rate mortgages (75% of US) explains the impact on consumer spending differences between the 2 nations.

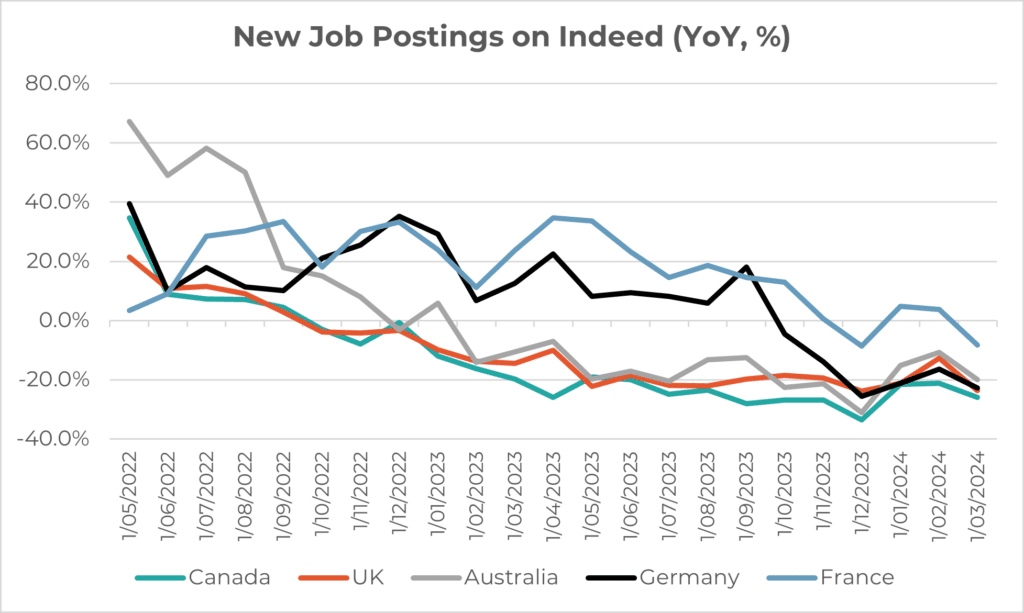

Labour Markets

A final note is on labour markets. We’ve all heard the “labour hoarding” story which followed COVID, as immigration stopped and “deglobalization” trends began to emerge, the demand for labour shot up and labour supply fell. This pushed up wage growth and brought power to the employees.

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

We’re starting to slowly see this wane across all these respective nations, even the US. Labour supply increasing via immigration is also helping this “tight” labour market loosen – which means wage growth won’t be as high, potentially weakening households especially as inflation volatility has spiked again. Can the central banks thread the needle by cutting rates in time before consumption and labour markets get too weak? Time will tell…

Quarterly market update | Q1 2026