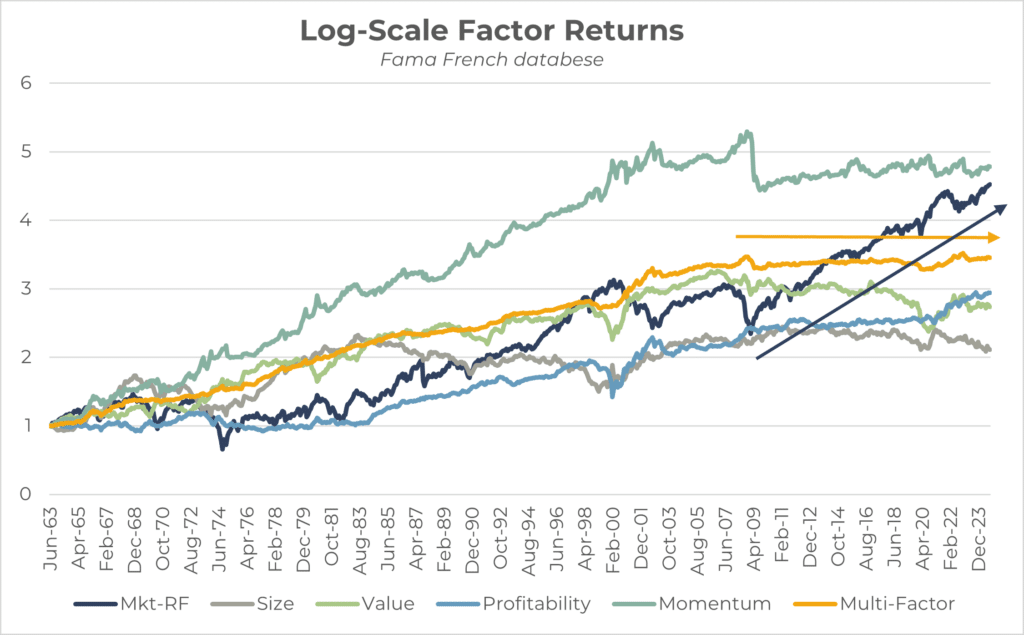

Factor investing promises higher risk-adjusted returns for investors with a long enough time horizon. A “long enough time horizon” is quite a vague statement, how long exactly is “long enough”?

Source: Fama French Website, Innova Asset Management

As we’re currently witnessing, one must be patient to have a higher chance of reaping the rewards of factor investing. A simple 50% value and 50% small caps strategy has faced a prolonged period of underperformance relative to growth and large-cap stocks, extending over 15 years. This extended drawdown can test an investor’s ability to endure, particularly when considering the higher fees associated with factor-based strategies compared to a passive market-cap-weighted index.

So, let’s say you do have that kind of time horizon, and you’re excited to beat the market because leaning into slightly riskier stocks leads to this outcome in the long run. The next battle to face is an internal one and reflects the title of this piece, which is why factor investing is ironic.

Behavioural Biases and Behavioural Risks

Factor investing claims to reap rewards partially through “behavioural biases” of investors and capitalising on the mispricing’s in the cross-section of stock returns as a result of these biases. As an example:

Anchoring: tendency to accept and rely on the first piece of information given to you.

Conservatism: tendency for one to revise beliefs poorly based on new evidence e.g. give the new information 50% of the value of the initial information.

These two biases lead to over and underreaction to news (Hong and Stein, 2002), and hence mispricing’s in asset prices. It’s the phenomenon that academics and practitioners typically refer to when explaining the momentum anomaly, where stocks continue to rise (fall) after they’ve previously been rising due to the underreaction to particular good (bad) news.

This is an example of how participants in asset markets may be caught offside by their own behavioural biases and hence the “mispricing’s” in the cross-section of stocks.

On the other side, there are behavioural biases of factor investors, or in general those making asset allocation decisions, who are promised higher risk-adjusted returns from investing in factors – but cannot stomach a potential long stretch of pain. Besides, no pain no gain, right? No one said factor investing was a free lunch, there’s a reason why these groups of stocks deliver a greater return, it’s because they’re less palatable for the average person. Everyone wants to get rich owning Apple, Amazon and Google, but because of this very fact, these stocks may not make you rich.

So overall the point I’m trying to make is that factor investors are actually vulnerable to behavioural risks, ironically. They have to battle the temptation to switch their ugly “value” stocks to glamorous “growth” stocks during that 15-years which is the current period of underperformance one has accepted when sailing into the factor investing sea. We’re currently seeing this exact scenario of the longest value drawdown in history, leading to comments such as “this time is different for value”. Whilst I don’t believe this is true, it very much encapsulates the” behavioural risk” of factor investing, which is how long one lasts in this factor drawdown period.

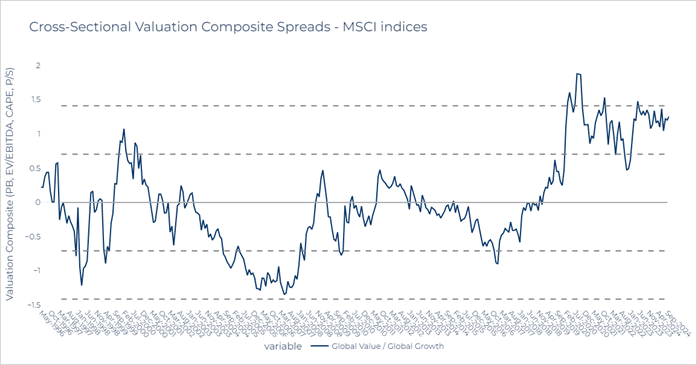

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

Above illustrates this prolonged outperformance of growth companies over value companies, where we now sit at a wide valuation gap (positive Z-Score means growth is expensive, negative Z-score means value is expensive).

Negative tracking error in portfolios can be a catalyst of this behavioural risk to factor investors, who are seeing the market (which is free) consistently outperform their multi-factor fund for a stretched period of time. Consistent negative tracking error can be unsettling and raise questions.

Standing at today, do we still have to wait 15 years and is factor investing dead?

Whilst timing factor exposures is a notorious topic within academia and practitioners, and is clearly difficult, the wide gap in the valuation between value/growth and small/large companies begs the question: at similar levels historically, how long does a factor investor have to wait to reap the rewards of tilting towards “riskier” companies (e.g. factor investing)?

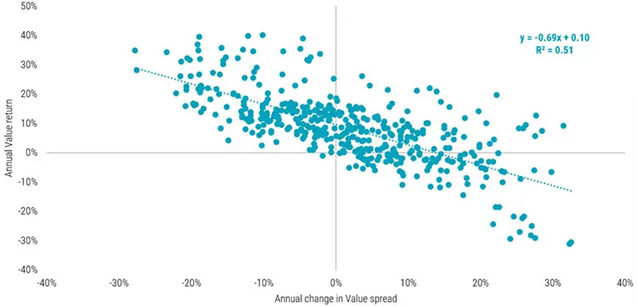

Source: Robeco Asset Management

Robeco show in their 2024 article “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated” that changes in value spread are negatively correlated to excess return for value. We can expect this mean reversion in relative valuations to happen in the coming years as the cost of capital is significantly higher than the previous decade, where growth had it’s time in the sun at super low borrowing costs. As we know, growth stocks have the bulk of their cash flows further out and hence more heavily discounted by a discounted cash flow model, unlike value (cyclicals) who fluctuate with the economy more and have their cash flows closer to today.

But Growth stocks have higher earnings growth!!!

It’s also been proven extensively that growth expectations out 5-10Y versus the realized growth following are always vastly different. Investors overestimate growth expectations of growth firms relative to value firms, though between 1990-2022, the average realized growth spread is around 80% less than what the market expects (AQR, 2022).

So not just valuation

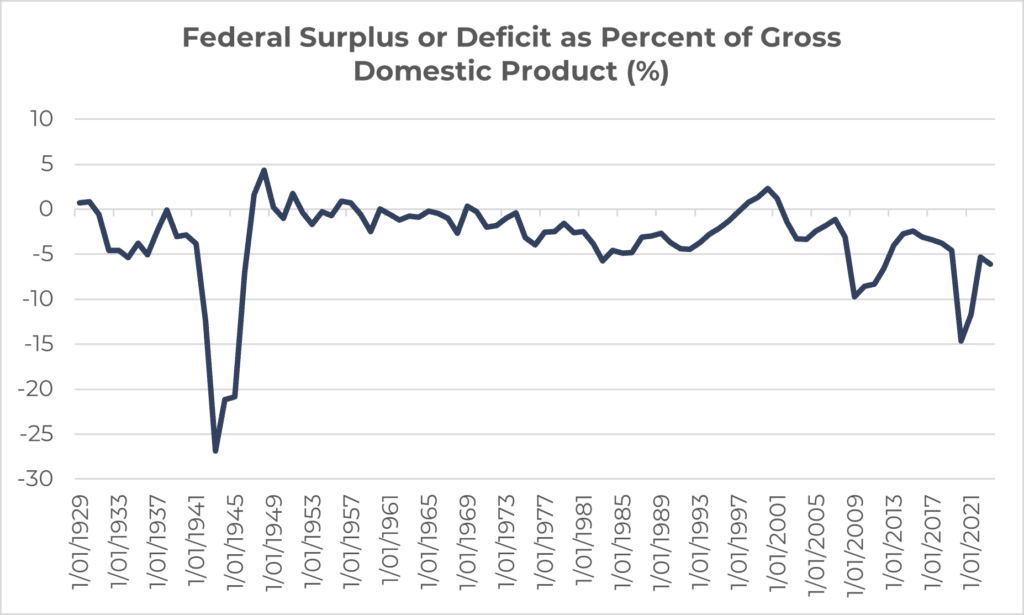

Many have pointed out that value and size should outperform because of these wide valuation gaps, but it happens to coincide with a significant shift in macroeconomic regime where the US government is having to extend their deficits, and “fiscal dominance” is upon us.

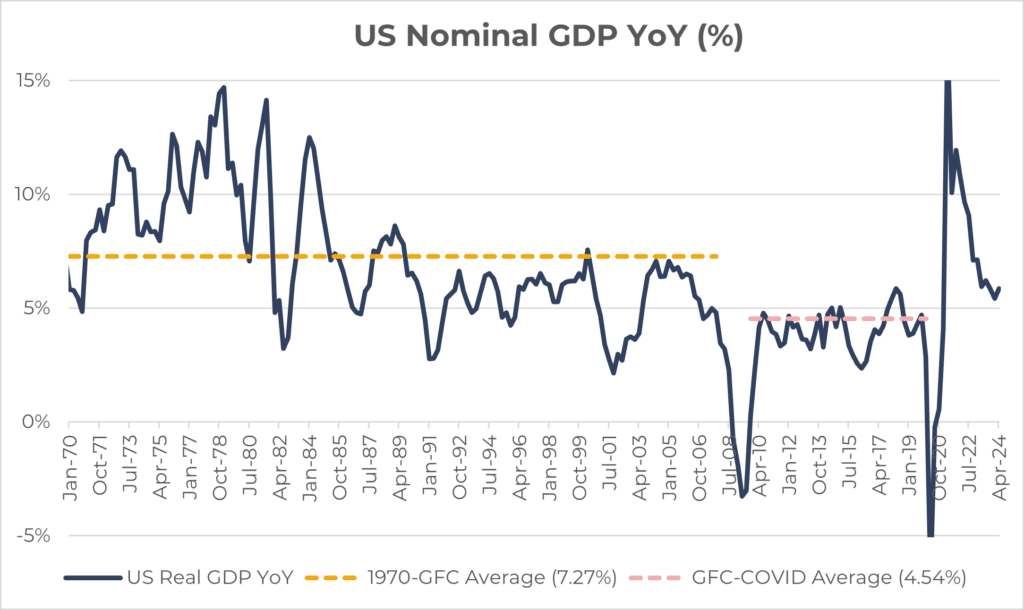

Source: Fred, Innova Asset Management

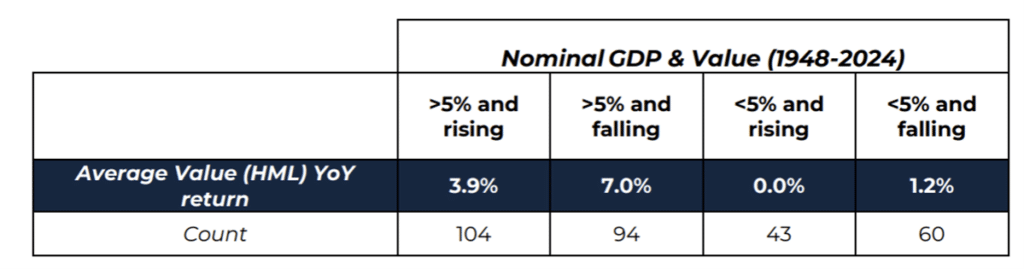

Historically, periods of relative nominal growth have been associated with value regimes. The regime ahead of us will most likely be characterised by higher inflation and relative higher growth compared to the post GFC period where deflation was more of a worry than inflation. Below we can see how value behaves across that 5% nominal growth breakpoint:

Source: Fred, Innova Asset Management, Fama French Website

Secular drivers of a higher structural inflation regime are emerging from deglobalization, ongoing geopolitical tensions, and demographic shifts, all of which generally exert upward pressure on prices. The US currently allocates more of its budget to interest payments than to military spending, which already surpasses the combined military expenditures of most other nations. This defensive spending underscores the heightened global geopolitical tensions and coincides with a period of supply chain reshoring and two active wars.

Source: Fred, Innova Asset Management

Whilst it was clear that supply-chain issues were the caused of the very significant inflation shocks in 2022, these secular factors alongside a world driven by excess liquidity and government spending may lead to structurally higher “entrenched” inflation pressures. I’m not referring to the 8% levels we saw, but perhaps closer to 3-4% rather than 2-3% as we saw in the past decade.

So, I should time value?

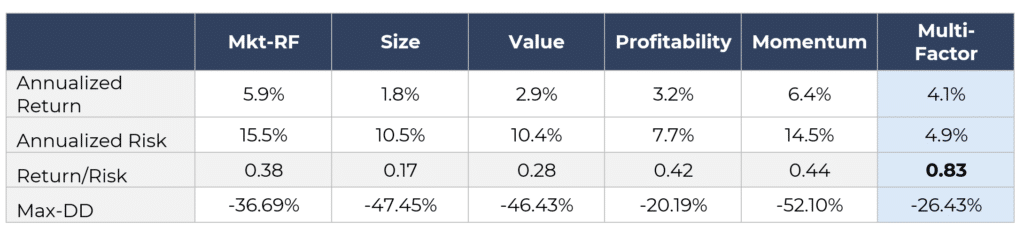

Overall, one of the biggest benefits of factor investing is the way they work together. They tend to work countercyclically, making them perfect in combination with each other. How effective exactly is this diversification in terms of risk-adjusted returns, and how did a multi-factor portfolio do from 1963-2024?

Source: Fama French Website, Innova Asset Management

Clearly, taking a diversified approach to factor investing seems superior due to the time-varying nature of factors. Whilst the past 10-15 years have been painful broadly, one can expect based on history that some of the out of favour players such as value and size should pull their weight in the coming decade.

It should also be noted that historically when market-cap indices such as the S&P 500 become as concentrated as they are, “equal-weighted” indices of the same set of companies tend to heavily outperform in the following 10 years.