For many people, achieving financial stability is a lifelong goal, but unconscious biases and emotional

decision-making can secretly sabotage even the best laid plans. Financial advisers see it every day in the behaviour of clients who struggle with a wide range of behavioural biases. Biases such as anchoring, loss aversion, short-term bias, and herding can derail even the best laid financial plans.

Advisers must take on multi-faceted roles that not only include teasing out client goals and making financial plans but managing their behavioural biases. Investing strategies may fund goals, but only human behaviour can achieve them.

Why are clients like this?

Our brains are wired this way for a reason – to make sense of an overly complicated and dangerous world. Many decisions in our evolutionary history are needed to be made quickly to survive.

Famed psychologist Daniel Kahneman referred to it as System One: the fast, intuitive and automatic way of thinking that we use to make most decisions. By way of contrast, System Two is slow, deliberate and analytical.

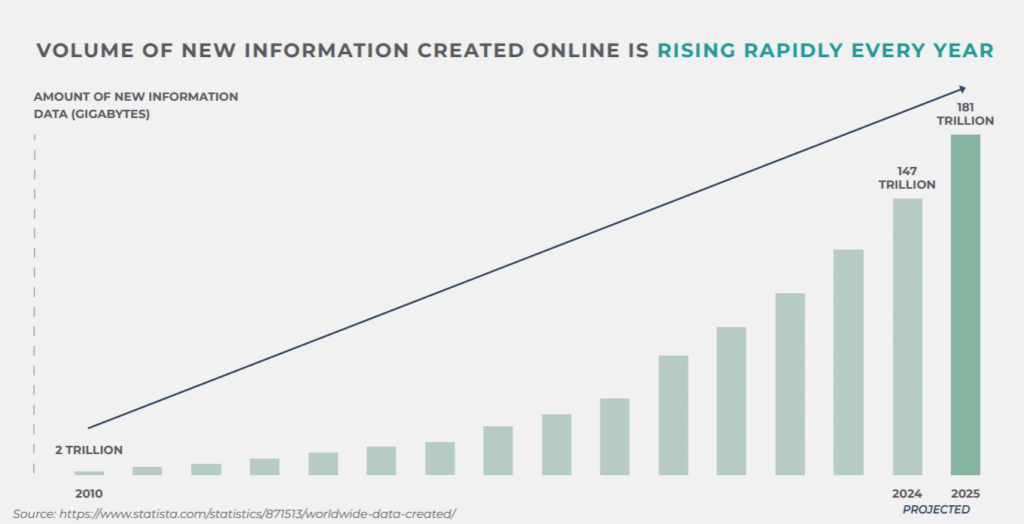

While the conscious mind can process approximately 50 bits per second, the unconscious mind that helps make decisions can process an estimated 11 million per second. All of that processing power is increasingly swamped by the rising volume of information that now floods the world.

Mental shortcuts or heuristics allow people to make sense of this information and make decisions quickly and efficiently. In many instances these shortcuts work, but they can also lead to behavioural biases that destroy wealth.

“Psychology is such an important part of the plan,” says Acadia Wealth Advice financial adviser and principal Chris Fallico, “because you can design the best financial plan and investment portfolio and cashflows – and it’s straight out of the textbook and a university lecturer will give you 100 per cent – but if it can’t be implemented in the real world because of people’s biases or psychology around money – it’s useless.”

A look at some common behavioural biases

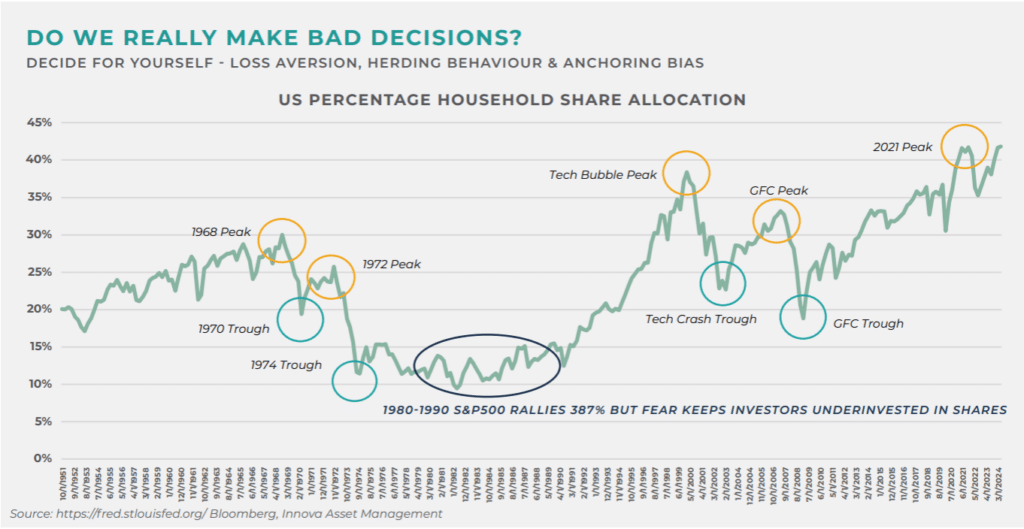

Advisers constantly see the impact of investors’ emotions and behaviours in their day-to-day jobs, but it

is also reflected in big data sets. The graph below shows how US investors have consistently made poor decisions over decades.

The US share market rallied almost 400 per cent over the 1980s but memories of the extreme sustained

losses during the 1970s arguably kept investors out of the market. This is loss aversion in action: the pain of a loss hurts far more than the pleasure of a gain. It is a particular driver for most retirees who become more loss averse over time and as their savings hit a peak.

In fact, loss aversion was ranked the most common client bias by advisers who attended a recent Innova presentation at the Ensombl All Licensee PD Day. A range of other biases also explains why investors more commonly followed the market on the way up. Over confidence and herding behaviour are reasons why investors increased their share allocations as the market rose well beyond its underlying fundamentals, such as the tech bubble and global financial crisis.

It helps explain why people tend to buy more shares and other investments after they’ve gone up in price (when they’re more expensive), whereas they’ll tend to buy more items in shops when they’re on sale (when they’re cheaper). Anchoring bias also leads to these poor decisions. It sways investors to overly focus on one piece of information, overlooking new information that would make them question their course of action. In fact, the anchor may have no relevance to the decision at all.

(If you want to read more about the psychology behind behavioural biases, we recommend five books here. )

A better way to manage clients and redefine risk

These behavioural biases are simply ways people use to understand the world and then take action to achieve their goals while managing risks. But risk is often defined by the academic world in highly narrow and theoretical terms. Risk is not just volatility – it is far more broad-based and multi-faceted depending on a client’s individual goals and time horizons. The traditional risk tolerance measure is severely limited and only captures a small portion of what drives clients.

Other factors such as the chance of not achieving their goals by failing to take on enough risk (goal risk) and their ability to take on risk (risk capacity) are also crucial. These multiple goals can only be captured as part of a goals-based investing framework. The second part of this two-part series will explore how to build this type of framework which also works with the innate behavioural biases of investors rather than against them.