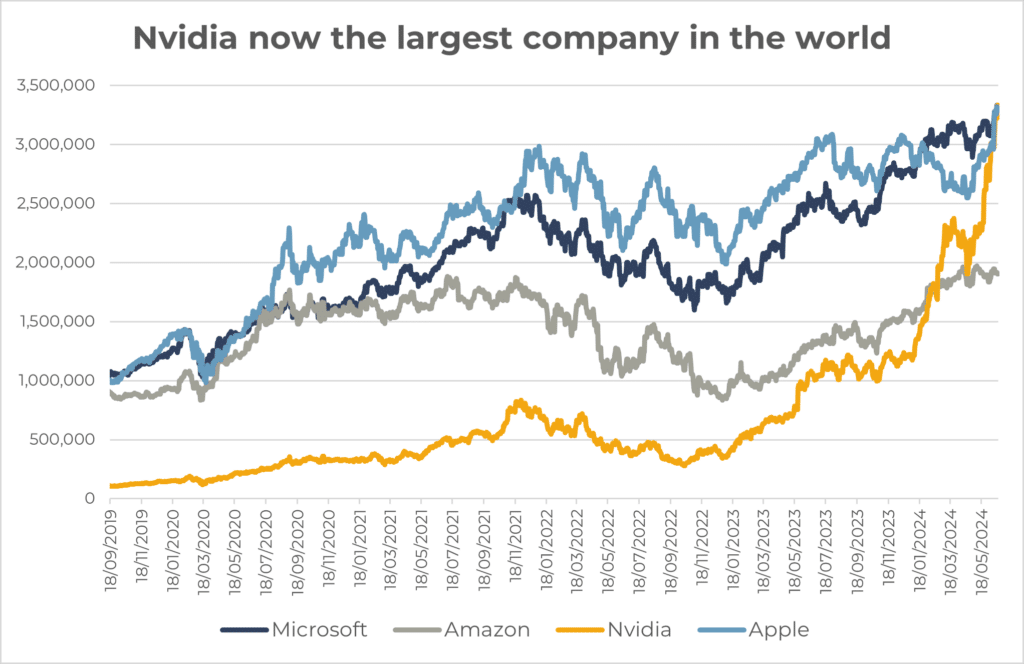

As Nvidia has just become the most valuable company in the world, we sit and reflect on the frenzy that we’ve witnessed over the past 1.5 years. Clearly many think that AI’s impact on work for the average white-collar Joe is akin to the industrial revolution’s impact on the blue-collar work force.

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

Background

On November 30th, 2022, ChatGPT 3 was launched to the world for free, and reached over 100 million users within two months of release. Since then, the topic of generative AI, large-language models and the “potential productivity boost” of it all, has made its way into almost every post-work drinking session.

Source: Innova Asset Management, Google Trends

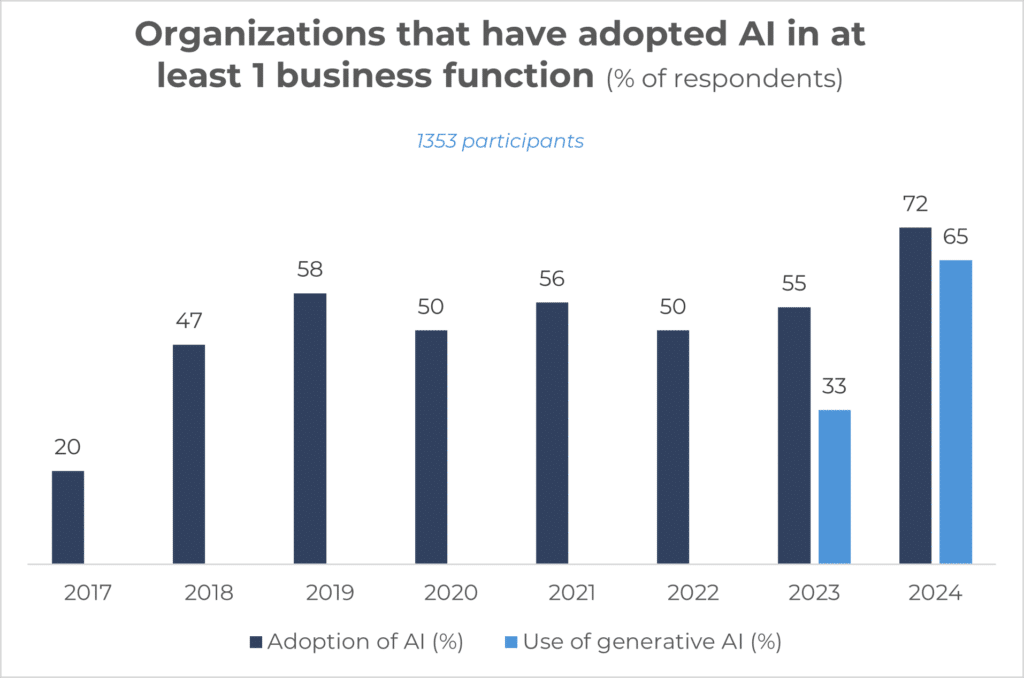

The new-age arms race for greater computational power has not only captivated the tech industry but also investors, who are looking to take stakes in companies operating in the AI space. One of the key arguments has been that AI will enhance operational efficiency across all companies, boosting productivity and driving earnings through the roof…though time will tell if the immense speculation for this narrative is justified.

Source: McKinsey, Innova Asset Management

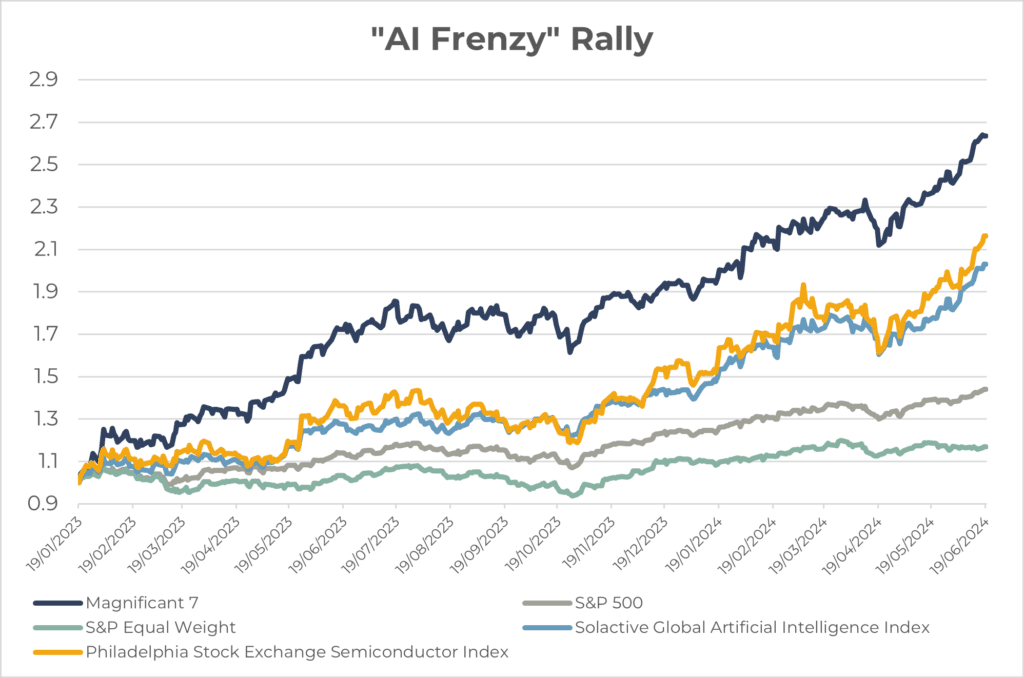

Because financial markets are discounting machines, we’ve seen this speculation play out massively over the past year or so, since the “AI frenzy” started. Many have drawn parallels to the tech-wreck due to the hugely stretched valuations of AI-related tech companies, though this time is a little different, in that these companies actually have earnings growth and strong foundations in their fundamentals – compared to the plethora of companies with no earnings in the early 2000s.

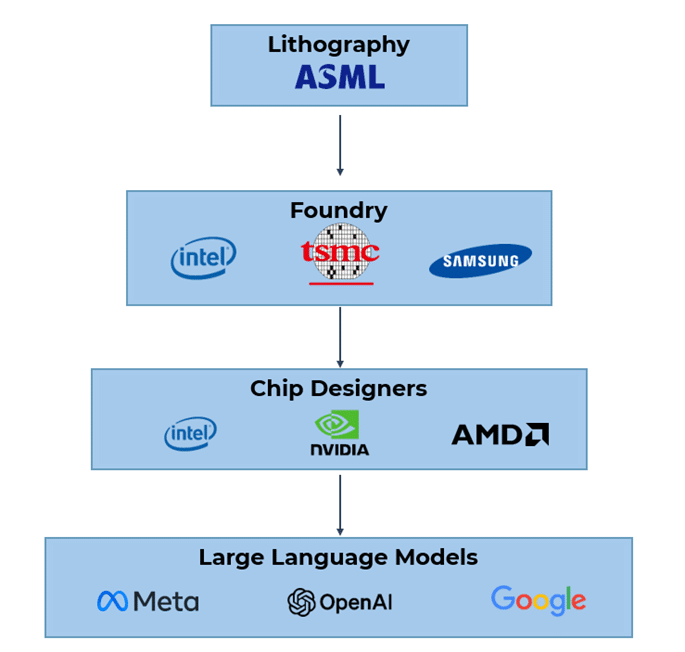

The immediate key beneficiaries of this vast demand will be those manufacturing, producing, developing and designing the semiconductor “chips” that power large language models (but not the only beneficiaries going into the future, which I will discuss further in the piece).

Semiconductor Supply Chain

The below visual outlines the core companies involved in powering the large language models and data centres of the modern world, from the maker of photolithography machines (ASML) to the manufacturers (TSMC, Samsung) to the designers who use the manufacturers (Nvidia, AMD), and further the AI modellers (Google, Open-AI, and thousands of other new companies).

Notably, there are 2 main types of these end-users or “hyperscalers”:

- Data Trainers (Chat GPT, those who create and train the models, very energy intensive and computation power heavy)

- Inference (Using existing models, using APIs to create applications for inference within certain fields – where a lot of the future lies, e.g. Tik Tok, AWS, Meta).

Technological Advancements and Macro-Finance

Technological advancements can have a significant impact on financial markets and the macroeconomy. The early stages of newer technologies are filled with speculation and generally lots of uncertainty. The question is when businesses and households will truly reap the rewards of these new shiny toys – and for us as asset allocators, whether these advancements will have a material impact on the future earnings of a company and future productivity of an economy, or whether this is all “hype”, and the material impact is just wishful thinking. Academics have already established that AI adoption has led to increased sales or operating efficiencies (Babina et al., 2024a; Mishra et al., 2022). We’ve seen a huge increase in R&D relative to other sectors which also presents a risk of disappointment.

To be able to price in the potential benefits of AI into productivity and company performance, we must know when these tools will be integrated into practical operations, which is extremely difficult. Therefore, it seems quite bizarre that markets have begun to price this thematic close to perfection, without any certainty nor clarity on the time-horizon for which the material impact will settle in.

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

Is there a potential extra level of riskiness in AI stocks that aren’t being priced in?

The way the Nasdaq has behaved over the past year is more in line with a defensive sector that is not rate sensitive, being driven by what we know now as the Magnificent 7 – who all leverage a fair bit of AI. Leader of the pack is of course Nvidia, the poster child of this whole craze.

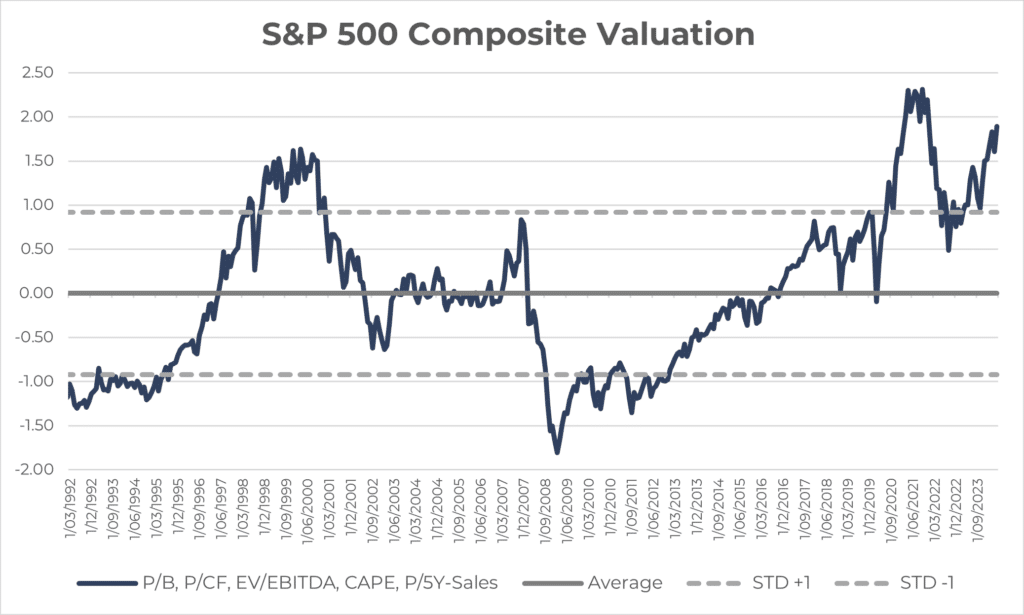

What we know from history is that companies that are connected to the semiconductor industry tend to be cyclical, as their earnings cycle trend alongside global growth. Due to this higher earnings volatility, these sectors should be compensated via higher returns. We’re currently presented with significant risk in the event of a Mega-Cap earnings miss, which we’re still yet to truly see in the recent cycle. Usually this wouldn’t be too much of a concern (earnings miss), but due to valuations being at approximately 2 standard deviations above their 30-year average on the S&P 500, the market expectation is quite high, and sentiment is able to be disappointed to the downside, unlike in early 2023 when expectations were super low, and upside surprises brought risk assets back on board.

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

Source: Innova Asset Management, Bloomberg

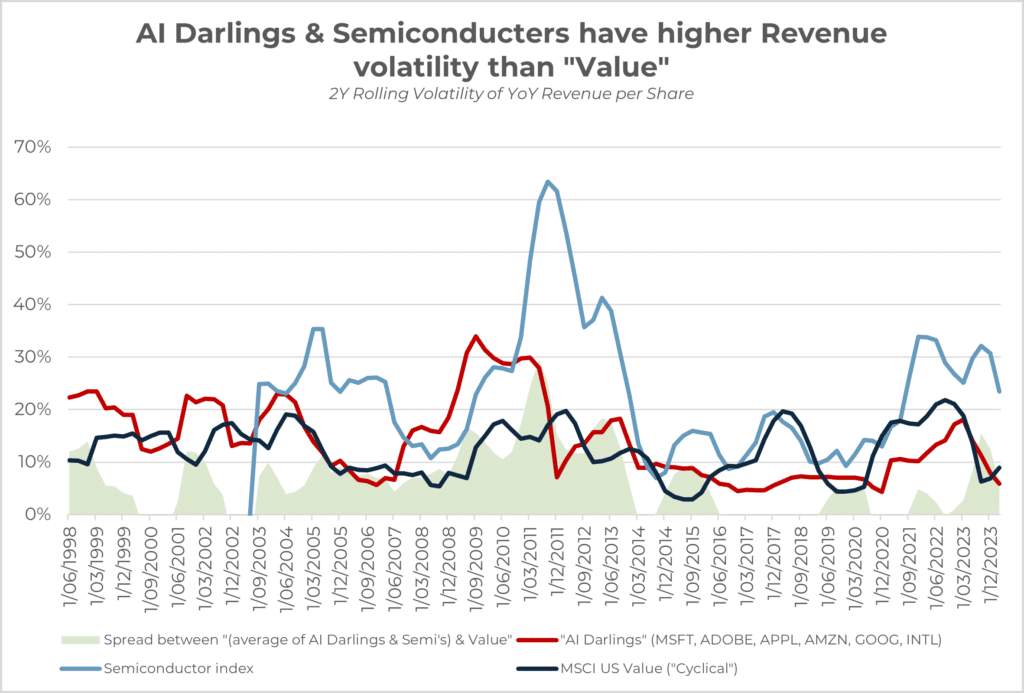

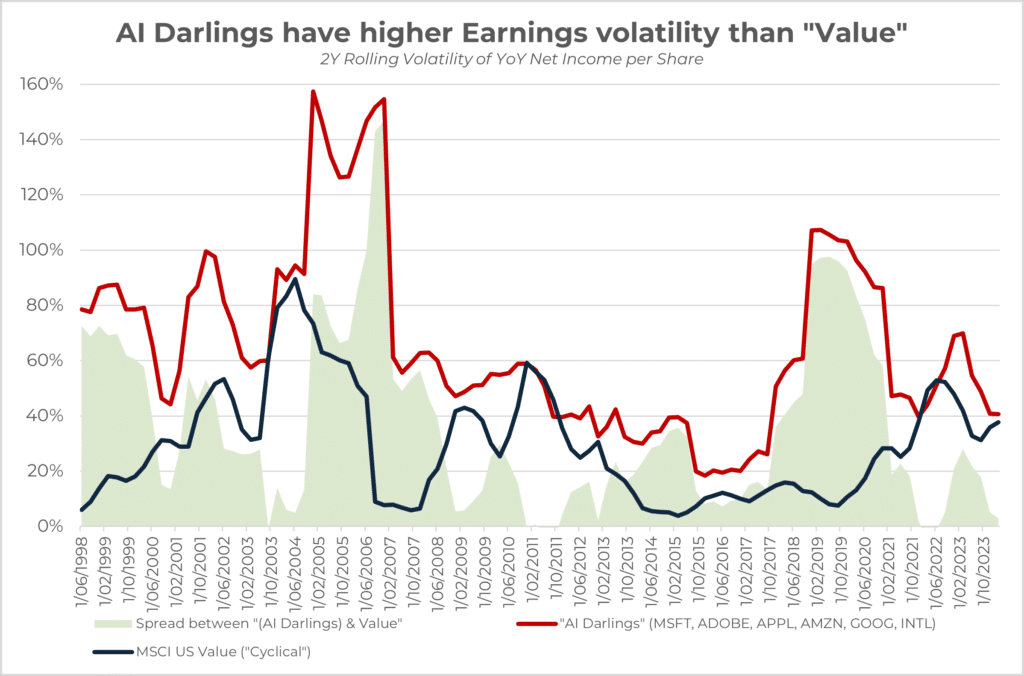

It can be observed that earnings and sales volatility for these companies are no lower than cyclical companies (higher revenue volatility in 77% of the rolling months) and have a close relationship to the business cycle. In particular, the sector shows increased volatility during period of stress around the tech-wreck, GFC and now in 2023. Modern asset pricing attributes historical outperformance of the value factor to increased cyclical risk, so drawing from similar insight, we would argue that additional compensation would also be required for “these companies”.

A little leaf from asset pricing literature

What we know based on a century of empirical studies is that change in valuation ratios are entirely driven by future expected returns (risk premiums) in the long term while future dividend growth is unpredictable (Campbell, Shiller, 1988; Cochrane, 2008).

Taking a quote from Jason Hsu at Rayliant (previously at Research Affiliates) that embodies the behaviour of the investors around the Mag 7:

“The other common thread—one which seems driven more by marketing optics than theory or data—is that all of the selected quality characteristics are viewed as being attractive firm attributes, those characteristics investors would generally be willing to “pay up” for. Implicit in the design is that the high-growth and high-profitability firms with low debt and conservative accounting practices are underpriced and thus generate high returns! This should raise alarms for the economists among us. It’s not just a free lunch, it’s a free feast!”

History tells us that during tighter financial conditions and overstretched market sentiment, downside earnings volatility can be expected, however we have not seen that play out yet. Any cracks in the AI-related companies’ earnings could spell serious trouble, given the bids that are put on these companies, and historically low equity volatility. The current multiples we observe often reflect instances where companies have consistently surpassed earnings expectations. Despite these positive earnings surprises for a few firms, the market has occasionally struggled to sustain rallies during these earnings releases, a concerning sign.

To round up

Overall, what we’re saying is that whilst there may be a genuine potential productivity benefit from AI applications, we suspect many investors are buying the Mag-7 and other related AI companies for their defensiveness and “blue-chip” nature – but as we all know there’s no free lunch in investing. Clearly these companies exhibit higher earnings volatility, and therefore are riskier, which investors should be cognisant of.

As the sentiment (valuation) of AI companies increase towards historical highs, the risk premium is reduced, hence one should expect a lower future return. As risk managers, it’s our responsibility to take risk where we are compensated for it, though this basket of stocks currently aren’t doing so on a forward looking basis. Risk premiums suggest there is little premium to be harvested, even though we observe persistently higher earnings volatility in semiconductor and “AI” darlings – especially around times when market concentration is at all time highs in these types of names.

References

Babina, T., Fedyk, A., He, A., Hodson, J., 2024a. Artificial intelligence, firm growth, and product innovation. Journal of Financial Economics 151, 103745

Campbell, J.Y. and Shiller, R.J., 1988. The dividend-price ratio and expectations of future dividends and discount factors. The review of financial studies, 1(3), pp.195-228.

Cochrane, J.H., 2008. The dog that did not bark: A defense of return predictability. The Review of Financial Studies, 21(4), pp.1533-1575.

Hsu, J., Kalesnik, V. and Kose, E., 2019. What is quality?. Financial Analysts Journal, 75(2), pp.44-61.

Mishra, S., Ewing, M.T., Cooper, H.B., 2022. Artificial intelligence focus and firm performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 50, 1176–1197

Quarterly market update | Q1 2026